What are Lynx?

Lynx are medium-sized cats, with tufted ears and a short tail. There are four species of lynx around the world, and the Eurasian lynx is the largest, typically weighing 17-28 kg (about the size of a Border collie). Males tend to be slightly larger than females.

Life and habits

Eurasian lynx keep a low profile, resting in cover during the day to avoid people. Where wild prey is very abundant, lynx densities can reach up to five cats per 100 km2 (an area roughly the size of the Isle of Rum), but lower densities are the norm, and lynx are always rarer than smaller carnivores like foxes.

Lynx are woodland creatures, but don’t need huge areas of undisturbed forest. Switzerland’s largest lynx population is found in the north west Alps with a similar amount of forest to parts of Scotland.

Lynx are generally solitary animals. They mate in the spring and give birth to two or three kittens in mid-May or early June. The kittens spend their first two months in dens before accompanying their mother further afield.

Once independent, lynx may live up to 17 years, although few wild lynx live that long. Most adult lynx deaths in Europe are due to traffic accidents, disease or hunting by humans.

Diet

The Eurasian lynx is an ambush hunter, typically eating around one deer per week. They can hunt red, fallow or sika deer but struggle to tackle healthy red deer stags and show a clear preference for roe deer.

A variety of other animals – including foxes, hares and woodland grouse – also make up a smaller proportion of the lynx’s diet.

When did Britain lose its lynx?

The youngest lynx fossils found in Britain include a skull from Sutherland that’s been dated to the 3rd century AD, and bones from North Yorkshire which tell us lynx were present in England as late as the 5th or 6th century AD. But it’s possible that some lynx clung on until much later, leaving only intriguing cultural clues, before their final disappearance went unmarked by history.

Among these clues, a 9th-century stone carving from the Isle of Eigg shows a large, tufted-eared cat – possibly a lynx – being chased on horseback. An account from Auchencairn in 1760 also mentions a yellow-red cat, three times the size of a domestic cat, that some suggest may have been a lynx.

Hunting, widespread deforestation and the decline of wild prey eventually led to the loss of the lynx from Britain. Lynx also disappeared from most of Europe, except for a few strongholds in Scandinavia and the Carpathian mountains of central and eastern Europe.

Comeback Cats

Since the early 1970s, lynx have been returning to more and more of Europe, both naturally and with the help of planned reintroductions. Today, there are around 9,000 Eurasian lynx in Europe and they are found in almost every large European country. But Britain’s island status means they will never return to Scotland unless we bring them back.

Why reintroduce lynx?

Lynx once lived in Scotland, but human activities drove them to extinction, so a growing number of people feel a duty to restore this missing species.

Scotland has become one of the most wildlife-depleted countries in the world, ranked 213th out of 240 countries for the state of its biodiversity. Reintroducing lynx would support our international commitments to restore nature, bring a range of ecological and economic benefits, and enrich our experience of wild nature closer to home.

What are the ecological benefits?

As top predators, lynx influence the behaviour and numbers of their prey, creating healthier, more dynamic ecosystems. Their return could help restore many missing or frayed connections in Scotland’s tattered food webs.

Could lynx help control deer?

High deer numbers prevent woodlands from regenerating and can contribute to peatland degradation, stalling progress towards climate and biodiversity goals.

The National Lynx Discussion found that lynx could play a role in reducing negative deer impacts, but only by complementing – not replacing – human management.

How might lynx affect other wildlife?

To help us understand how lynx might affect wildlife in Scotland, we can look at their impact elsewhere.

In Scandinavia, lynx have reduced fox numbers, allowing a rise in capercaillie, mountain hare and black grouse populations, with similar effects possible in Scotland.

Lynx also increase the supply of large carcasses – currently scarce in Scotland – recycling key nutrients and providing an important year-round food source for many other species.

How would people and communities benefit?

Lynx would make Scotland’s landscapes feel wilder, while also attracting visitors and boosting local economies.

Although lynx are typically hard to see, this doesn’t seem to reduce their appeal – a bit like Nessie, who is estimated to generate over £41 million for Scotland annually. In the area around Germany’s Harz National Park, lynx attract between £7.5 and £12.5 million in tourist spending each year.

How do people feel about lynx?

Recent surveys suggest a growing majority of the Scottish public want lynx to be reintroduced. The latest poll in 2025 found 61% of Scots in favour of a lynx reintroduction, including more than 50% of Scots in every region of Scotland. Just 13% were opposed, with the remainder undecided.

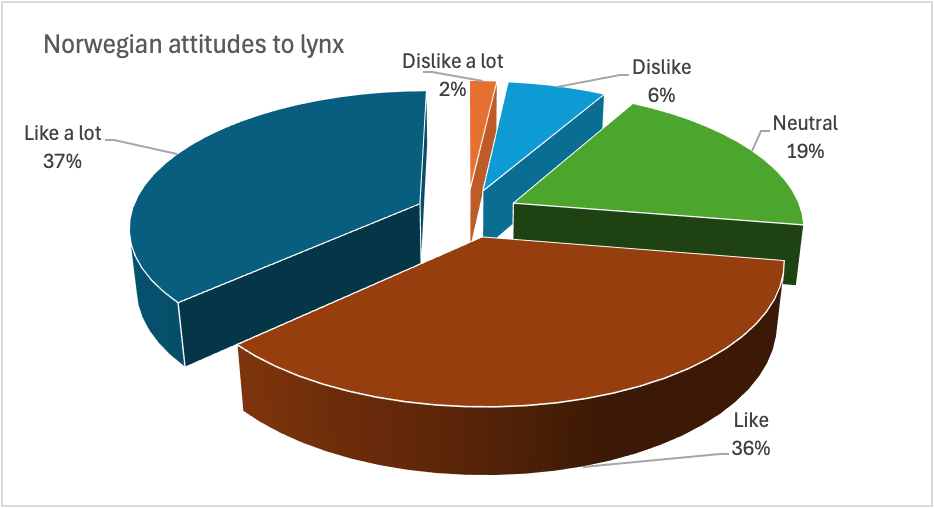

Where people already live with lynx, support is even higher. Elsewhere in Europe, 72% of Norwegians and over 74% of Swiss respondents said they like living with lynx. As one German visitor to Harz said: ‘Knowing that these animals are there and may be watching me is a great feeling.’

Attitudes to lynx among people who report living close to lynx in Norway (Source: 2017 Gallup poll commissioned by the Norwegian Government)

Are there risks?

Overall, people find lynx to be one of the easiest large carnivores to live alongside and polls show they are well-liked by most people who live close to them. However, any reintroduction naturally attracts questions and concerns. Here are some answers to commonly asked questions and areas of concern about lynx.

Could lynx harm people or pets?

Like foxes, a lynx could kill a domestic cat but, since lynx generally avoid settlements, the risk is very low. Lynx rarely attack dogs, and would usually only do so if they felt threatened. Lynx are not a threat to people.

What are the risks to lynx themselves?

All animals would be health-checked before release and would be released into habitat with enough wild prey. The risks to lynx are therefore minimal.

Are there any threats to native species?

There are no records of Eurasian lynx causing declines in capercaillie or wildcats elsewhere. In fact, in parts of Scandinavia, lynx have been credited with increasing numbers of capercaillie, black grouse and mountain hares by preying on foxes that would otherwise hunt them.

Scotland’s National Lynx Discussion concluded that there are enough deer across most of Scotland to prevent lynx from needing to hunt smaller prey, and that lynx could potentially benefit threatened species by helping to control fox numbers.

Is there a threat to gamebird shooting?

Red-legged partridges or pheasants could be taken by lynx around release pens (where birds are housed before being released for shooting), but lynx would be less likely to cause problems than other native predators, since they would be much rarer.

They are also woodland creatures, and do not hunt on the open hill, so are unlikely to prey on significant numbers of red grouse. Any measures to secure gamebirds against predators like wildcats should also be effective against lynx.

Scotland’s National Lynx Discussion concluded that gamebirds are not a significant part of the lynx’s diet where deer are freely available, but that an agreed approach to manage any conflicts would be needed.

How might lynx affect deer stalking?

Lynx are specialist deer hunters, prompting some concerns about potential impacts on deer stalking traditions and businesses.

Scotland’s National Lynx Discussion concluded that lynx are likely to have minimal impact on traditional red deer stalking on the open hill. However, because lynx would likely be a protected species, some deer management within woodlands could face new restrictions, which would need to be carefully managed.

Lynx could also reduce the number of trophy roebucks available in some areas, which may affect stalking income. Any such impacts would need careful monitoring.

Would lynx take livestock?

Lynx do kill livestock – most often sheep – but the numbers killed vary greatly between countries.

In most countries, annual sheep losses attributed to lynx are relatively low. Losses In Norway are exceptionally high, but these mostly happen when sheep graze in the forest, unprotected. When sheep are fenced into fields or are grazed away from woodland, it’s relatively rare for lynx to attack them. Lynx also show a clear preference for hunting deer and sheep predation is even less common where deer are abundant. Scotland supports much higher deer densities than Norway, reducing the risk of attacks on sheep. Additional information on this topic can be found in our [LINK] Concerns booklet.

Lynx may take unsecured chickens, but this is unusual. They may also prey on farmed deer, but this can be prevented by electric fencing. Lynx attacks on larger livestock are virtually unheard of.

Scotland’s National Lynx Discussion highlighted that, even if lynx only kill small numbers of sheep, the impact on individual farmers could be significant. Managing this would require a transparent and responsive approach, including financial support measures developed in collaboration with farmers.

What could a reintroduction look like?

Lynx reintroductions have been taking place across western Europe since the 1970s, creating a wealth of knowledge about how such reintroductions can best be managed. Scotland now has an opportunity to borrow from more than half a century’s experience, to develop a reintroduction plan that works best for nature and people in our own country.

How many lynx would be released?

A licensed lynx reintroduction would begin with just a few animals – probably two males and two females. The aim would be to release four more animals each year, until around 20 lynx had been released (enough to create a healthy founder population).

Where would they come from?

Lynx reintroductions can use either wild-caught or captive-bred animals.

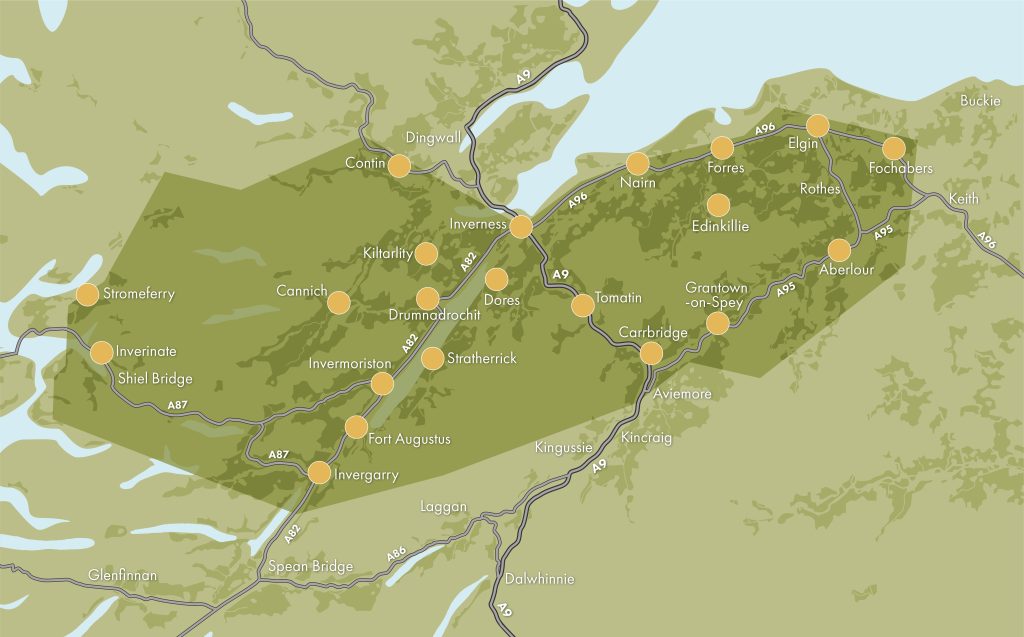

Where would they be released?

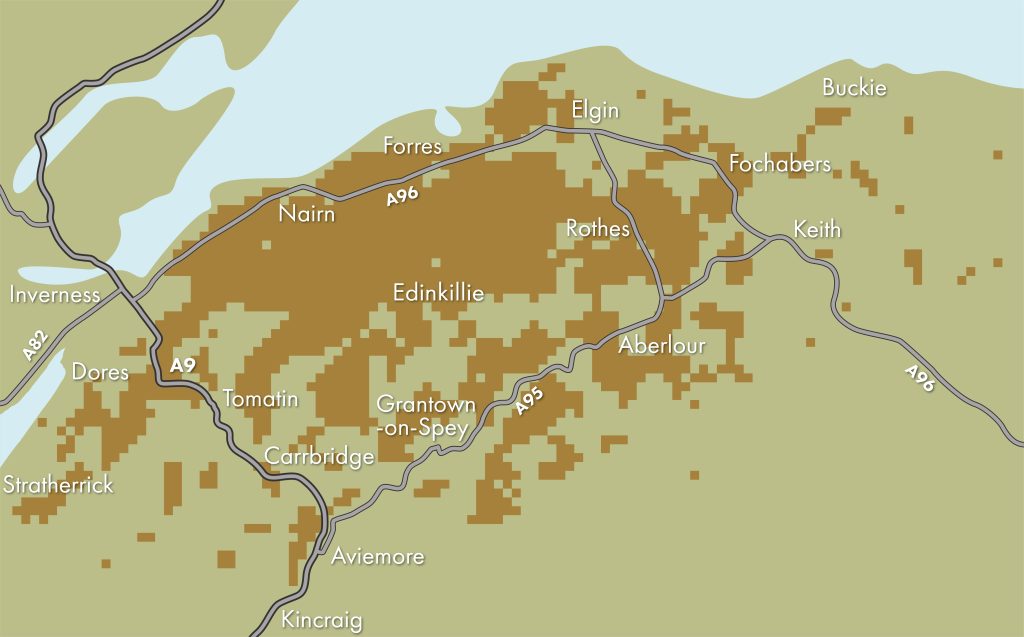

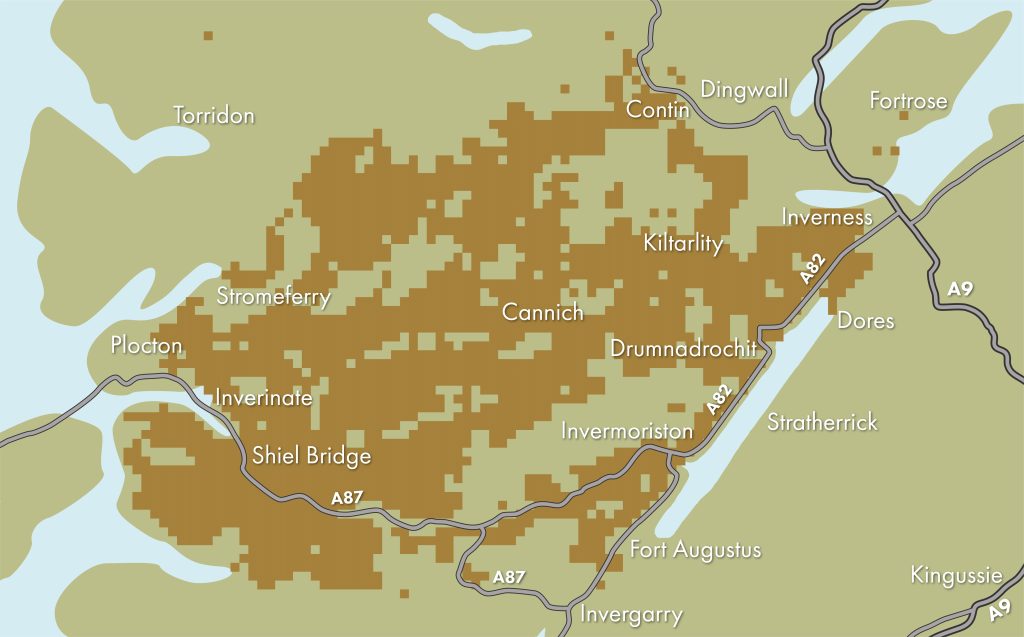

The Highlands and Moray contain some of the best lynx habitat in Scotland, with extensive areas of woodland and abundant wild prey. Take a look at the map below which shows the extent of our Consultation area and the woodland habitat network within this. Lynx could be released at one or several sites, in quiet locations, away from major roads.

Where would they go?

Lynx can cross rivers, roads and fields to move between patches of woodland so, over time, they could return across large parts of northern Scotland. There is currently enough habitat and prey in this region to support at least 250 animals – the same number of lynx currently found in Switzerland. However, population growth and range expansion would likely be quite slow.

The maps below show the possible distribution of a lynx population five years after a release either to the west or east of Inverness.

The Central Belt is likely to present a barrier to effective lynx dispersal between the Highlands and the South of Scotland.

What would limit the population?

Like other top predators, such as otters or eagles, lynx numbers would be limited by the availability of food and territories (den sites and shelter). Once these became limited, the lynx population would reach a natural balance.

How would they be monitored?

The released lynx would be fitted with tracking collars and monitored long term via an extensive system of cameras. Monitoring would be a key part of the project, to track any negative impacts – such as sheep predation – alongside any benefits, like increased tourism revenue and wider biodiversity gains.

How would a lynx reintroduction be funded?

All costs would be met by the Lynx to Scotland project for the initial 5-10 year reintroduction period. After that, management responsibility would pass to the Scottish Government.

Would there be an exit strategy?

Yes. In the unlikely event that negative impacts could not be managed, an exit strategy would see lynx being removed from the landscape. But the intention would be to proactively respond to any issues or conflict to prevent this scenario from occurring.

National stakeholders recommended that if a reintroduction takes place, it should follow a phased release programme with appropriate monitoring, adaptive management and a fully funded exit strategy.